Youth and injecting drug users

I wrote this research brief while a senior writer at Family Health International (now FHI 360). Click here for a link to the original PDF.

Most injecting drug users start the practice before age 25, yet few HIV prevention programs targeting injecting drug use focus on youth.

A recent World Health Organization (WHO) analysis of HIV prevention programs among youth found few programs focusing on young injecting drug users (IDUs).[1] A review of current intervention projects among IDUs also found few that targeted youth — either to prevent the initiation of injecting (primary prevention) or to reduce risks of HIV associated with injecting drugs (i.e., harm reduction). Yet, sobering statistics indicate the importance of reaching youth before they start injecting or using drugs that lead to injecting, and if they have started, finding ways to relate harm reduction strategies to youth circumstances.

Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, injecting drug use (IDU) accounts for one in three new cases of HIV. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, some 80 percent of all new HIV infections come from IDU, with high rates also reported throughout the Middle East, North Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[2] Youth under age 25 make up about seven of every 10 injecting drug users in Russia, Central Asia, and Central and Eastern Europe, with youth also a high percentage in Bangladesh and Indonesia.[3] IDU is also surfacing as a problem in Africa. A 2005 study among 51 youth injecting heroin in the capital of Tanzania found that a central reason was the “growing importance of youth culture.”[4]

Of the estimated 13 million people injecting drugs worldwide, about three to four million live with HIV. Those who inject drugs contract HIV by sharing contaminated injecting equipment and drug preparations, as well as through sexual intercourse. In 2008, the United Nations found rates of HIV infection among IDUs ranging from 31 percent to 61 percent in Vietnam, Ukraine, Thailand, Nepal, Belarus, Brazil, and Indonesia.[5]

Why youth are vulnerable

IDUs of all ages report that they first injected drugs in their teens or early 20s. A WHO study among more than 6,400 IDUs in 12 cities in five continents found that between 72 percent and 96 percent said they first injected drugs before age 25.[6] Risk factors for starting to use drugs include homelessness, dropping out of school, and unemployment. Many youth begin sniffing or smoking opioids, then start injecting because they assume it will be more cost effective. In fact, the amount of drugs needed when injecting soon surpasses the sniffing habit.

Curiosity, peer pressure, and availability contribute to first injections.[7] Youth seek out peers or siblings who already inject and ask them for help. First injections rarely occur alone; they usually take place in a social situation, with a young person first being injected by a friend, relative, or sexual partner. Rituals can develop around injecting (e.g., a group mix); young people take part because they want to be members of the group.[8] On these occasions, they may share or use nonsterile injecting equipment. Young IDUs are more likely to share needles and syringes than older IDUs but are less likely to have contact with an HIV prevention program.[9] They are also more likely to be injected by someone else and, as a result, are less in control of decisions that affect sharing.[10] Several U.S. studies suggest that young women are more likely to share needles than young men.

Some regional factors also affect youth injecting drugs. In Central Asia, youth are in close proximity to about 90 percent of the world’s opiate supply, with about 12 percent of drugs produced in Afghanistan passing through Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Opioids are readily available and relatively inexpensive (e.g., US$1.50 per dose in Tajikistan).

Many young IDUs are involved in the sex industry — often to support their drug addiction — and report multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex. Recent research among 52 IDUs in Bangladesh and Indonesia by Family Health International (FHI) found that they commonly engage in unprotected commercial sex. Most of the IDUs are young. While almost 90 percent said they were in a “serious” relationship, 75 percent of those with a regular partner said they were also having concurrent sexual relations. This illustrates how IDUs can contribute to moving the epidemic into the mainstream population.[11]

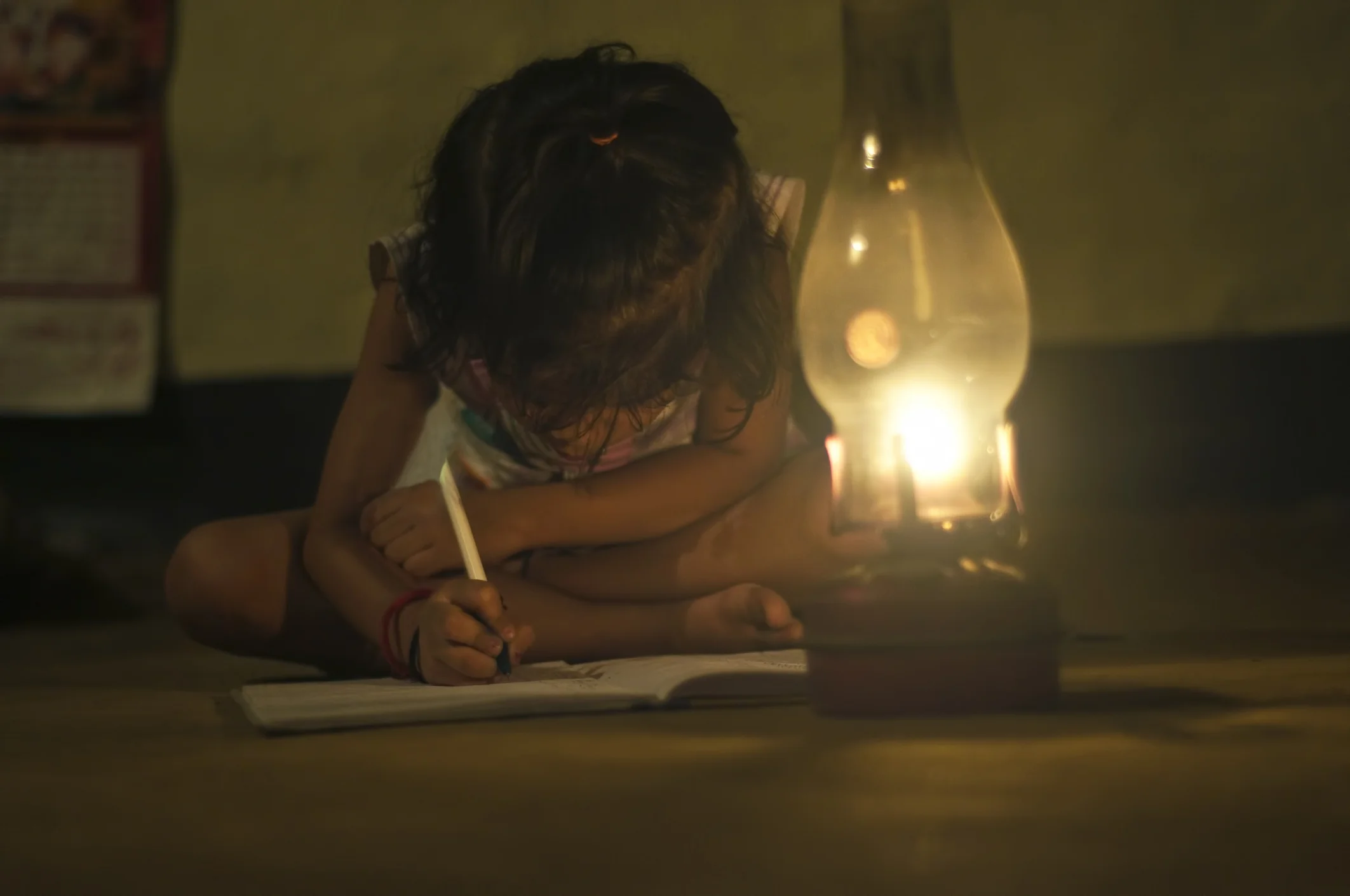

Young people who inject drugs are often unaware of risks associated with their behavior, including the severity of health problems they may encounter. Since drug use is illegal and often stigmatized, young IDUs tend to eschew mainstream society and vice versa. Most drug treatment services cater to adults or addicts, and the needs of young IDUs are often overlooked — especially those in the early stages of injecting or those who do not consider themselves addicts.[12]

Primary prevention programs

Primary prevention of IDU involves reducing supplies or demand for drugs. Most HIV prevention projects focus on demand. An important window of opportunity is to target young non-injecting drug users who are at risk of transitioning to injecting.

Population Services International (PSI) has supported several prevention efforts in Central Asia through a project called Break the Cycle, based on a United Kingdom program developed by Neil Hunt. The project aims to prevent young people from starting to inject drugs by targeting enablers — IDUs who play a role in initiating others. In a 2006 study of IDUs in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, 86 percent of IDUs reported receiving help on their first injection, with roughly one-half reporting that they were aided by a sibling or cousin and one-third reporting that they were helped by friends. Each IDU helper assisted about 2.7 people to initiate injecting drugs over the previous six-month period. A UNICEF/Ukraine project, also using this intervention, found that 83 percent of new IDUs received help from a more experienced user on their first injection; each IDU helper assisted about 3.6 new injectors.[13]

Break the Cycle encourages IDUs not to help others start injecting. It also asks them not to inject in the presence of non-IDUs or talk about the “benefits” of injecting. In Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, PSI has determined that if the program can convince 50 IDU helpers not to help others initiate injecting, it can prevent about 135 people from initiating IDU each six months. This, in turn, would reduce cases of hepatitis C, HIV, and deaths by overdose.

Also in Central Asia, PSI works as a key partner of the Alliance for Open Society International’s Drug Demand Reduction Program. PSI targets young people living along major drug-trafficking routes who are at risk of becoming injecting drug users. The program pays particular attention to young people who socialize with IDUs on a regular basis, under the assumption that those youth are at very high risk of initiating IDU themselves. Youth centers provide a wide range of activities to reduce their vulnerability to IDU initiation. Peer educators play an important role at the centers because they are perceived as credible sources of information on the dangers of injecting drugs.

Prevention among potential injecting drug users is also under way in parts of Africa. In Tanzania, the Zanzibar Association of Information against Drug Abuse and Alcohol (ZAIDA) focuses on prevention of substance abuse among vulnerable youth through peer education and community outreach, with assistance from FHI/Tanzania. Peer educators, some of whom are former substance abusers themselves, provide life skills education that emphasizes HIV prevention and the negative consequences of drug use. Community dialogues accompanied by theater performances also help raise awareness. Former youth drug users who become peer educators may be empowered in this role but may also need support to continue abstaining from drug use.

Harm reduction programs

Harm reduction programs involve policies and programs that try to reduce negative consequences of drug use. Needle exchange programs are a form of harm reduction that has been effective in reducing HIV transmission rates.[14] The U.S. government currently does not fund needle exchange programs. Harm reduction strategies also involve psychosocial approaches, which could include education, peer support, addiction counseling, case management, economic assistance, support groups, and other services. Some medical specialists use pharmacotherapies, such as methadone maintenance therapy, but this treatment may not be appropriate for those younger than age 18.

Treatment programs can help reduce HIV infection. The U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse reports, “Drug injectors who do not enter treatment are up to six times more likely to become infected with HIV than injectors who enter and remain in treatment.”[15]

In Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan, a Friendly Pharmacy Program launched by PSI provides IDUs with vouchers they can exchange at pharmacies for sterile injecting equipment and condoms. Since 2006, more than 154,000 needle-syringe combinations have been distributed to 2,500 IDUs, about 30 percent of the target population. About 12 percent of those reached in Kyrgyzstan and 8 percent in Tajikistan were younger than 25, indicating that the program is reaching many young and new IDUs.

In Iran, UNICEF and a local nongovernmental organization, KPYA Federation of Youth Health, recently sponsored a program to prevent HIV among young IDUs in Mashhad, Iran, through peer education. Through a two-day workshop, the program trained IDUs to educate others about the dangers of sharing contaminated drug injecting equipment. The IDUs then went to drop-in centers and ruins where other youths congregate to inject drugs. They talked to peers about what they had learned and distributed pamphlets, sterile syringes, and condoms. Nearly 600 IDUs have been trained as peer educators. Referrals to drop-in centers for needle exchange and methadone maintenance treatment have increased by 54 percent.[16]

More attention needed

Few countries have initiated programs that reduce harm or drug demand among young people, even though this is the period when most injecting drug use begins. A 2008 United Nations (UN) study puts forth nine key principles of drug dependence treatment, hoping to raise awareness of drug dependence as a health disorder.[17]

A report from a 2006 technical consultation led by UN groups calls for a minimum package of services for young IDUs that is “confidential, private, nonjudgmental, and adolescent-friendly … creating a protective environment where youth can talk openly about risk behaviors, receive accurate and appropriate information from peers and adults in their community, and access services without fear of being maltreated or fear of negative consequences.”[18]

Young people are still at the stage of experimentation and can learn more easily than adults to make their behavior safe or to adopt safe practices from the start. To help address these needs, programs need to pay more attention to young people for both primary prevention and harm reduction. Such action can help to address a key segment of HIV infection, young people beginning to inject drugs.

REFERENCES

1. UNAIDS Inter-Agency Task Team on Young People. Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People. (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006)307.

2. UNICEF. People Who Use Injecting Drugs. 2008. Available from: www.unaids.org/en/PolicyAndPractice/KeyPopulations/InjectDrugUsers/.

3. UNICEF, UNAIDS, WHO. Young People and HIV/AIDS: Opportunity in Crisis. New York: UNICEF, 2002; Weibel W, Koester S, Pach III A, et al. IDU Sexual Networks in Bangladesh and Indonesia: Epidemic and Intervention Implications. Bangkok: Family Health International/Asia Region, 2008.

4. McCurdy SA, Williams ML, Kilonzo GP, et al. Heroin and HIV risk in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: youth hangouts, mageto and injecting practices. AIDS Care 2005;17(Suppl 1):S65-S76.

5. UNICEF. Children and AIDS: Country Fact Sheets. New York: UNICEF, 2008.

6. Malliori M, Zunzunegui M, Rodriguez-Arenas R, et al. Drug injecting and HIV-1 infection: major findings from the multi-city study. In Stimson G, Des Jarlais D, Ball A, eds. Drug Injecting and HIV Infection. London: UCL Press, 1998.

7. Gray R. Curbing HIV in drug-driven epidemics worldwide. Presentation at AIDSMark End of Project Conference, Washington, DC, December 5, 2007.

8. Howard J, Hunt N, Arcuri A. A situational assessment and review of the evidence for interventions for the prevention of HIV/AIDS among occasional, experimental and young injecting drug users. Unpublished paper. UN Interagency and Central and Eastern European Harm Reduction Network Technical Consultation on Occasional, Experimental and Young IDUs in the CEE/CIS and Baltics, 2003.

9. Bailey S, Huo D, Garfein R, et al. The use of needle exchange by young injection drug users. Epid and Soc Sci 2003;34(1):67-70; Guydish J, Brown C, Edgington R, et al. What are the impacts of needle exchange on young injectors? AIDS and Behav 1999;4(2):37-146.

10. Guydish J, Kipke M, Unger J, et al. Drug-injecting street youth: a comparison of HIV-risk injection behaviors between needle exchange users and nonusers. AIDS and Behav 1997;1(4);225-32.

11. Weibel, 2008.

12. Global Youth Network/United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. HIV Prevention among Young Injecting Drug Users. New York: United Nations, 2004.

13. Gray, 2007.

14. Hurley SF, Jolley DJ, Kaldor JM. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. The Lancet 1997;349(9068):1797-800.

15. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. (Bethesda, MD: NIDA, 1999)20.

16. Nowbahar V, Matlabi E, Farzad J. HIV/AIDS Prevention Peer Education among Injecting Drug Users, A KPYA-FH Joint Project with UNICEF. Abstract for poster presented at 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights, Hyderabad, India, 29-31 October 2007.

17. UNODC, WHO. Principles of Drug Dependence Treatment. Vienna: UNODC, 2008.

18. UNAIDS Inter-Agency Task Team (IATT) on Young People. Accelerating HIV prevention programming with and for most-at-risk adolescents: lessons learned from the first global technical support group, Kiev, Ukraine, 24-26 July 2006. Unpublished paper. IATT on Young People, n.d.